All Boats Rise

The Unfolding of Tracy Weber at Portland State University

By Kurt Bedell

If you’ve worked at Portland State long enough — or wandered into the welcoming chaos of University Communications (UCOMM) on the eighth floor of the Neuberger Center (née Market Center Building) — you’ve probably crossed paths with Tracy Weber. If you haven’t, you’ve still likely felt her impact through the warmth of a campus event, her mentoring of a student, or one of the many conversations that make PSU more human.

Tracy’s career started in 1978, typing real estate licenses on a manual typewriter for the State of Oregon’s Department of Commerce. That first job then launched her into decades of work in higher education, touching a variety of institutions, including the University of Oregon, OHSU, and the University of Portland, before she found what she now calls her true “work home” at Portland State.

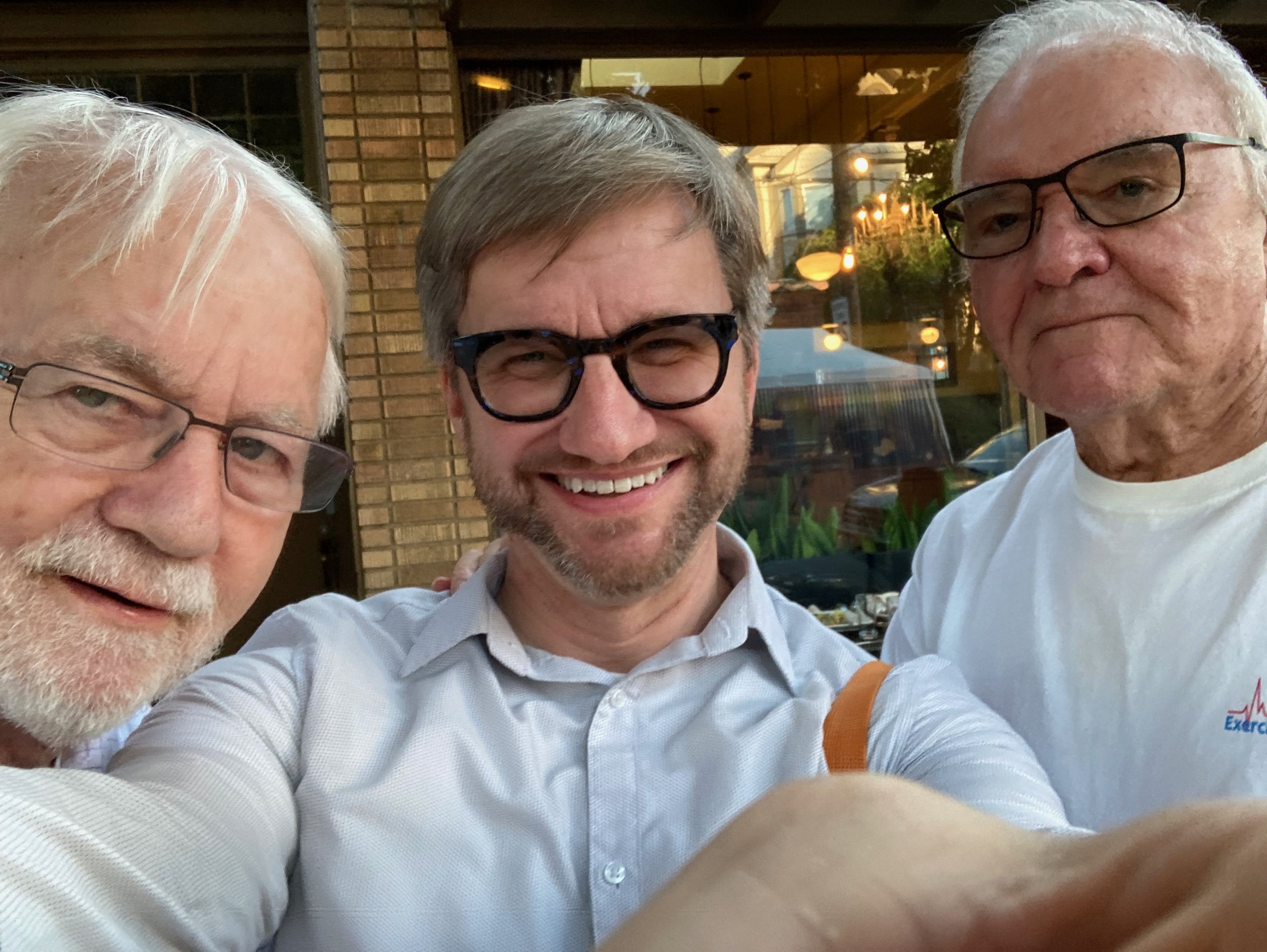

Tracy Weber at the University of Oregon, 1987.

Her PSU journey is a winding narrative of quiet resilience. After roles in The School of Business and its Food Industry Leadership Center (now the Center for Retail Leadership) — both of which ended when her position was eliminated by the same administrator — she eventually landed in UCOMM. She brought with her not only bruises but also a reputation for competence, candor and care. Within months, she felt something unfamiliar in her professional life: healing.

“UCOMM basically healed me,” she says. “I met more people across campus in that first month than I had in 13 years prior. It’s a family here.”

It’s not a word she uses lightly. Tracy isn’t your typical admin. She’s been a work mom, a mentor and sometimes the only adult in a student’s life who says the hard thing at the right time. Over 45 years, she’s supervised and supported well over a thousand students, many of whom still keep in touch, long after graduation.

“There’s nothing like watching someone come in as a freshman and leave as a rockstar,” she says. “To be even a small part of that transformation — it’s a privilege.”

For Tracy, Portland State’s mission is personal. “It’s the ‘all boats rise’ university,” she says, echoing a phrase she first heard from a colleague years ago that’s become her north star. “You change one person’s life, and you change generations.”

That’s not just philosophy — it’s lived experience. One of her favorite moments is watching first-gen graduates stand at commencement. “Every one of them represents a generational shift,” she says, her voice cracking slightly. “It’s everything this place is about.”

And yet, it hasn’t all been warm hugs with pomp and circumstance. Her time at The School of Business left deep wounds, including one particularly cruel episode when she was told her job was being cut — the day after signing to purchase her first house. She canceled the purchase, only to be told the next day her job was safe. Six months later, that job was gone for good.

The second time they eliminated her job, she left in tears. “I called my mom from the car, sobbing. I was thinking I just can’t keep beating my head against the wall.”

But through union protections, she landed again — this time in UCOMM. A bump that felt like destiny. The culture shock was immediate: Kindness. Inclusion. Coworkers who showed up when her mother was dying. People who actually rallied, not retreated.

UCOMM gave her back her belief — not just in herself, but in what a workplace could be. “The people here really care about each other. There’s no backstabbing. If anyone comes for one of ours, we circle the wagons.”

She found joy again, too, especially in PSU’s student events: the Tweetups, potlucks, and sweaty, chaotic, magical moments where hundreds of students were laughing and dancing because of something she helped bring to life. “That’s marketing,” she says. “When your heels hit the pavement and you’re giving people something fun to do — that’s how you tell the story.”

Looking back, Tracy calls higher ed a “higher-level watercooler conversation,” a place where ideas spark, people grow and futures get rewritten. Even now, as she approaches retirement, she’s learning from those around her. “If you’re open to it, the students teach you just as much as you teach them. They keep you rooted in the world as it is now — not the one you remember.”

She laughs about her evolution from typewriters to TikTok, but she’s not kidding when she says PSU has kept her future-focused. It’s why she’s proud to claim the university’s identity — even the controversial ones. When a local critic dubbed PSU a “social justice factory,” she responded, “Hell yeah. I’d wear that on a T-shirt.”

Tracy’s story at PSU isn’t just one of survival. It’s one of reinvention, of giving and receiving grace, of standing in the turmoil of hard things and still choosing to lift others up. Her advice for anyone walking through these halls?

“Work with students if you can. It keeps you honest, grounded, and future-facing. And take advantage of what PSU offers — it’s not just a place to work. It’s a place to belong.”

And for Tracy Weber, that belonging made all the difference.

Disclosure: I used ChatGPT to help draft this piece, using one of my earlier articles as a model. The story, the edits, and the heart behind it are all mine.